Digital Product Passports sound simple…

Until you try to deliver one in a real industrial supply chain.

Because the hard part is not publishing a passport and generating a QR code. It is getting the underlying data to show up on time, in the right structure, with evidence, and with access rights that do not accidentally expose sensitive product information.

Our ShareAspace platform helps you do exactly that. It acts as the governed DPP data backbone, so you can collect supplier inputs with control, verify what you receive, and keep everything traceable to the product.

If you’re in heavy industry, this will feel familiar.

You are not dealing with one neat dataset.

You have:

- Multi-tier suppliers (and different levels of willingness to share)

- Variants and options that change what is true for the product

- Engineering change that keeps moving the goalposts

- Confidential content that cannot be shared broadly

- Different teams holding different pieces of the truth

So yes, DPP is a regulatory topic.

But the day-to-day work is a data and collaboration problem.

Most teams still treat DPP like a report they assemble at the end.

That is when everything goes sideways, because you’re chasing inputs across suppliers and systems with no agreed baseline for what counts as “in” and what evidence makes it defensible.

Before we get into a practical approach, it’s worth aligning on what the EU actually means by a Digital Product Passport, because the field list will not be identical for every product.

What the EU means by a Digital Product Passport?

Under the EU’s Ecodesign for Sustainable Products Regulation (ESPR), the Digital Product Passport is basically a digital identity card for a product (and sometimes its components and materials). It’s designed to make relevant product information accessible electronically, so it can be stored and shared with the right people. [1][2]

The practical takeaway: you need a way to define requirements per product, collect data across the value chain, and keep it current as products and supply chains change.

So what does that mean in practice? What actually goes into the passport, and where does it live today?

What goes into a DPP, and where it lives today

The EU is clear on the direction: the Digital Product Passport is meant to carry structured product information that supports sustainability and circularity, and it will be specified through product-specific rules over time. [1][2][3]

At a minimum, the Commission already points to the kind of information you should expect to manage: material composition, substances of concern, and practical information on safe use, recycling, and disposal. [4]

Here’s how that lands when you’re the team who has to ship it.

The DPP data buckets you will end up assembling

Think in buckets, not in one giant spreadsheet.

- Product identity and scope

What the thing is, which “version” you are talking about, and how it is uniquely identified (model, batch, item). This is the anchor that stops everything else drifting. [1][3]

- Material and substance information

Composition, substances of concern, and anything that determines handling, compliance, and end-of-life choices. [4]

- Sustainability and circularity characteristics

The characteristics the EU is trying to drive: durability, repairability, recyclability, and the attributes that sit behind those claims. Product-specific rules will define what “counts” for your product group. [1][3][4]

- Instructions that make the product safe and serviceable

How it can be used safely, how it can be maintained, and what matters at end-of-life (reuse, recycling, disposal). [4]

- Compliance and who-can-see-what

Not just “do we comply”, but how you expose the right information to the right audience. EU examples (like the battery passport) explicitly split information into access tiers, with some data public and other data restricted to authorities or parties with a legitimate interest. [5][6]

Where this data usually lives (and why it is never in one place)

This is where DPP stops being a QR-code project and becomes an integration and governance problem.

- PLM and engineering toolchain: product structure, variant rules, approved drawings and models, change history, released configurations.

- ERP and manufacturing systems: batch and serial context, supplier and manufacturing identifiers, production events.

- Quality, test, and compliance tooling: declarations, test reports, audit artefacts, restricted substance evidence.

- Supplier channels: documents and evidence you do not own, delivered late, in mixed formats, with gaps.

- Service and after-sales: service instructions, maintenance events, updates that affect what is “true” through-life.

The EU expectation of traceability and controlled access is exactly why this is hard: you are not just publishing information, you are maintaining a trusted link between the passport and the product definition as it changes. [1][3][6]

What “evidence” looks like in practice

In the real world, a value is only as good as what you can point to when someone challenges it.

Evidence tends to be things like declarations, certificates, test reports, and technical documentation. The trick is not storing a PDF or Excel somewhere. It is tying that artefact to the right product scope (model, batch, item), the right revision, and the right access rights so you can share it without oversharing. The EU’s direction on DPP access being managed on a need-to-know basis makes that point explicit.

Once you can name the data and attach the evidence, the rest is an operating model: define what you expect, then manage what you actually receive.

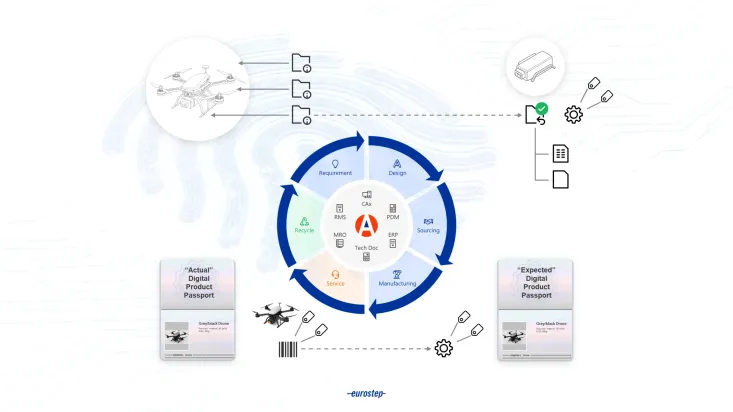

The operating model: define the expected DPP, then manage the gap

Now that you know the typical content, the mistake to avoid is treating it like a one-off compilation exercise.

A better approach is to define the “expected” DPP early. This is your target set of attributes, documents, and evidence for a product, agreed internally, owned, and trackable.

Then, as suppliers deliver, you compare the “expected” vs the “actual” DPP and manage gaps while you still have time.

That one shift turns DPP into a programme you can control, not a last-minute scramble.

Who should lead DPP in your company?

If DPP sits only in ESG, it often stalls in the data.

If it sits only in IT, it often stalls in the business.

A workable ownership model looks like this:

- Programme lead (accountable): scope, timeline, decisions, cross-functional alignment

- Sustainability and compliance: what must be declared, what evidence is needed, what can be disclosed

- PLM and engineering IT: product structure, change control, integration, traceability

- Supply chain and procurement: supplier onboarding, component and information requests, delivery governance

- Quality: validation discipline, review and acceptance, audit readiness

One simple rule: make one person accountable, but do not make one function responsible for everything.

Is there ROI, or is this just compliance?

Compliance is the forcing function.

But the same discipline that makes DPP achievable can also make operations less painful.

A strong DPP foundation tends to unlock:

- Less supplier chasing: fewer emails, fewer re-requests, less “wrong version” confusion

- Faster evidence retrieval: when someone asks “prove it”, you can actually prove it quickly

- Lower risk at deadlines: gaps are visible early, not when it is too late

- Better reuse of product data: stop rebuilding similar data packs for tenders, customer requests, and internal reporting

- More controlled transparency: share what is required, protect what is sensitive

No inflated promises. Just fewer avoidable fires.

Learn how ShareAspace can help you achieve your DPP implementation ROI:

* What happens next: We will reply to schedule a short call. You will get a recommended starting plan and a clear view of how to operationalise supplier collection, validation, and traceability.

How to make DPP work in practice

This is what “expected vs actual” looks like when you turn it into day-to-day work.

1) Get a DPP template you can manage

Outcome: you have one agreed set of information requirements per product group, with owners and acceptance rules.

Define:

- Categories of required information

- Specific attributes per category (format, units, allowed values)

- Guidance to suppliers on how to provide it

- What evidence is expected, and when

- What “acceptable” looks like, so review is consistent

This is how you move from “we should collect DPP data” to “we know exactly what we need, from whom, and by when”.

2) Make supplier delivery visible and controllable

Outcome: gaps show up early, and rework becomes predictable instead of chaotic.

Run supplier collection as tracked requests with named responsibilities and delivery status. You should be able to see:

- What was requested

- What was delivered

- What is missing

- What is overdue

- What is rejected, and why

3) Share the minimum required, without exposing the rest

Outcome: you meet disclosure needs while protecting IP and sensitive product information.

Set access rights by audience so partners see only what you explicitly share, and you can share evidence without oversharing. In competitive industrial supply chains, this is non-negotiable.

4) Turn submissions into trusted information

Outcome: When someone asks “prove it”, you can point to evidence and recorded decisions.

A robust workflow needs:

- Validation after delivery and before you share it onward (reviewed and signed off by the responsible person)

- Optional automated checks you define for completeness and quality (where it makes sense)

- Work-item-based review and sign-off by the responsible person (with decisions recorded)

- Evidence management that links documents and metadata to delivered attributes

5) Stay correct when change lands

Outcome: Design and supply chain change triggers updates, not rebuilds.

You need traceability from:

- Information requirements and templates

- Supplier deliveries (attributes plus evidence)

- Product structures, configurations, and revisions

- Product instances where relevant (including serialised items)

Because requirements change. Designs change. Suppliers change. If you cannot see impact, you end up rebuilding the passport repeatedly.

Model, batch, and item-level passports (why this matters)

This is a scoping decision, not a technical detail.

The level you publish at drives identifiers, update cadence, and how you handle change.

You should choose the right passport level up front, so you do not build a model-level approach and later discover you needed batch or serial control.

Model-level: You can start quickly with a stable baseline for a product type.

– Use this when the passport is mainly declared characteristics that apply across the product definition.

Batch-level: You can reflect what varies by production lot without turning every release into a bespoke exercise.

– Use this when key characteristics are tied to a run or shipment.

Item-level: You can support serialised products where what is true for one unit diverges over time.

– Use this when a specific unit needs its own identity and update path through-life.

The practical requirement is that you can hold a governed baseline and then attach batch or serial identifiers without rebuilding the programme.

That means one controlled product definition, linked to the right configurations and instances, with outputs generated from that governed baseline.

Why interoperability matters

Interoperability is not a slogan here. It is what makes a DPP programme survive real life.

Your DPP programme has to stay workable as endpoints, supplier patterns, and product-group rules evolve, without forcing a replatform. Here’s how and why:

Separate your governed baseline from your published outputs

Publish different views and formats without changing how you manage the underlying information.

Treat the passport as an output generated from governed information, not the place you maintain the truth.

In ShareAspace, that means configured views and Information Filters that control what information is presented and retrieved.

Keep integrations modular

Add or swap systems without rewriting the whole programme.

Your PLM, ERP, and supplier tooling will not stand still.

ShareAspace provides REST APIs designed for integrating with external systems, so you can evolve integrations without turning every change into a reimplementation.

Support multiple supplier exchange patterns

You may need to work with structured submissions, document-based deliveries, and packaged handovers in the same programme.

In ShareAspace, Share Packages support a governed sharing process where a responsible user is assigned, a work item is created, and the package can be reviewed before it is shared, with status visible in the Share Package module.

Design for change as routine

Updates become managed work, not a project restart.

With ShareAspace, this is change control and traceability applied to passport-relevant information, so your outward outputs stay aligned as the product definition, sourcing, or requirements move.

That combination is why ShareAspace lets you run DPP as a governed, multi-enterprise information flow with full interoperability in mind, not a one-off compliance exercise.

A quick self-check: are you DPP-ready yet?

If you can answer these quickly, you are in a strong place:

- What information do we need for this product group, and who owns each part of it?

- Which suppliers hold critical DPP data, and what do we need from each of them?

- Do we have a structured request for attributes and evidence, not a free-text email or a general product specification on PDF?

- Can we validate data quality before we accept it as true?

- Can we prove decisions and evidence later, without a scavenger hunt?

- Can we share what is required while protecting IP and confidentiality?

- When something changes (design, sourcing, requirements), can we see the DPP impact?

If you are stuck on any of those, you are not behind. You are normal.

Your fastest path to DPP progress

If you are building DPP readiness in:

- Automotive and EV

- Energy and power equipment

- Defence and aerospace

- Complex industrial manufacturing

We can help you shape a practical approach that fits your supply chain reality, protects sensitive information, and builds a trusted data foundation.

About Eurostep

Eurostep helps manufacturers and operators go from DPP intent to day-to-day execution by connecting people, systems and suppliers with governed data sharing.

Founded in Sweden in 1994 and now part of the BAE Systems family, we deliver ShareAspace. This proven, COTS collaboration layer dismantles information silos and enables secure sharing of product lifecycle data across enterprises, contracts, and supply chains. ShareAspace enforces access rights, traceability and configuration change control so you can share the right data with the right stakeholders through-life.

Trusted by engineering and operations teams at leading Nordic and European manufacturers for secure, multi-enterprise product data collaboration.

References

[1] EUR-Lex, Ecodesign requirements for sustainable products:

https://eur-lex.europa.eu/EN/legal-content/summary/ecodesign-requirements-for-sustainable-products.html

[2] European Commission, Commission launches consultation on the Digital Product Passport:

https://single-market-economy.ec.europa.eu/news/commission-launches-consultation-digital-product-passport-2025-04-09_en

[3] European Commission, Ecodesign for Sustainable Products Regulation (ESPR):

https://commission.europa.eu/energy-climate-change-environment/standards-tools-and-labels/products-labelling-rules-and-requirements/ecodesign-sustainable-products-regulation_en

[4] European Commission, ESPR Working Plan 2025–2030:

https://environment.ec.europa.eu/document/download/5f7ff5e2-ebe9-4bd4-a139-db881bd6398f_en?filename=FAQ-UPDATE-4th-Iteration_clean.pdf

[5] European Commission, Circular economy: New law on more sustainable, circular and safe batteries enters into force:

https://environment.ec.europa.eu/news/new-law-more-sustainable-circular-and-safe-batteries-enters-force-2023-08-17_en

[6] EUR-Lex, Regulation (EU) 2023/1542 on batteries and waste batteries:

https://eur-lex.europa.eu/eli/reg/2023/1542/oj/eng